When OpenAI unveiled ChatGPT Health in January 2026, it promised a “global grounding” in medicine, backed by 260 physicians across 60 countries. But for the African healthtech ecosystem, the launch highlighted a familiar friction: global AI is only as good as the data that built it, and that data remains overwhelmingly Western.

In a region where diagnosis often happens without a doctor, these gaps are dangerous. ChatGPT Health may master diabetes management, but it remains blind to the local surge in counterfeit antimalarials or the seasonal nuances of malaria transmission. It can recommend a blood test routine in London that is physically unavailable in Kano.

And still, the appetite for medical AI is already here. Nigerians are part of the 40 million daily medical queries OpenAI reports globally. In a country where 70% of the population self-medicates, millions now use AI to “pre-consult” before deciding if a clinic visit is worth the cost. This is where a new class of African GenAI startups—like KOYO, Awadoc, MyItura, and Zuri Health—are digging their moats.

The Intelligence Gap: standard vs. specialised

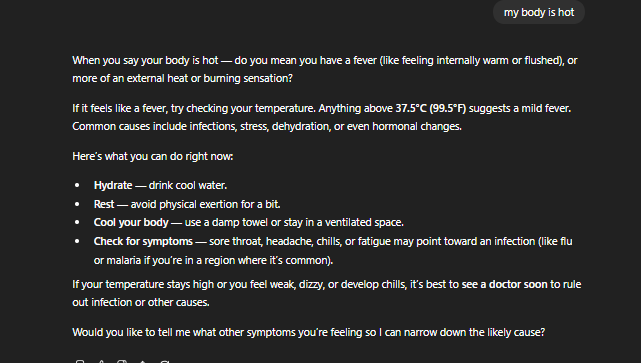

ChatGPT isn’t dumb. In fact, it’s often too helpful. When prompted with “my body is hot,” a general model like GPT-5.2 asks useful follow-ups: it clarifies if you mean a fever or a skin sensation, suggests hydration, and lists low-risk monitoring steps.

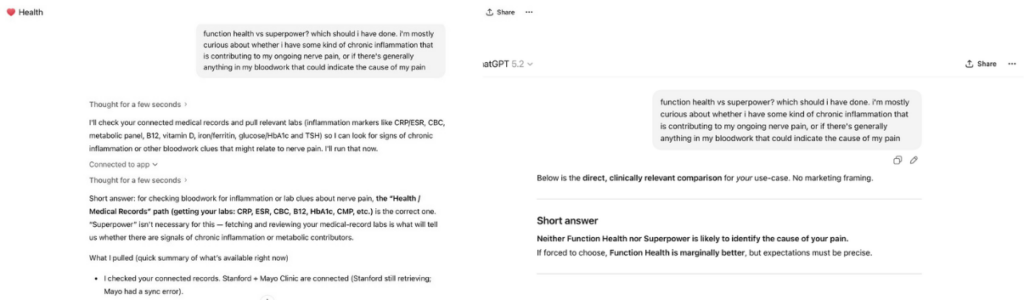

However, early adopters in the US are already noticing a “clinical friction” in the specialised ChatGPT Health project. While the base GPT-5.2 model feels intuitive and flexible, the “Health” version—integrated with infrastructure from b.well to index personal medical records—can feel more rigid.

This opens a competitive window for local players. While the “Big Three”—OpenAI, Anthropic (with its device-local Claude for Healthcare), and Google (with MedGemma 1.5’s 3D imaging)—are racing to make the best medical diagnosis a $20/month; they are scaling through generalisation.

Where generalisation fails

Three predictable gaps still prevent global LLMs from winning the African market:

- Hyper-local epidemiology: Malaria is endemic and seasonal. Advice that treats fever as “monitor for a few days” is acceptable in low-malaria settings; it’s riskier in places where malaria can deteriorate quickly. Local models must integrate seasonality and regional infection spikes into their triage logic.

- The supply-chain realities: When a user says they bought “amoxicillin from the chemist,” the implication in many Nigerian contexts can be radically different from a Western pharmacy purchase. Counterfeit or substandard drugs are a real, documented problem. An algorithm that assumes legitimate, standardised medicines will miss that variable.

- Logistical Care Pathways: Recommendations to “get a blood test” or “see a clinician” mean very different things in Lagos versus London. Local systems need to understand where diagnostics are accessible, which clinics provide free antenatal checks, or where a teleconsultation is a realistic next step.

This isn’t to say ChatGPT fails entirely; it often includes standard safety disclaimers. However, the difference between “general flu advice” and “local malaria triage” is the difference between a recovery and a crisis.

The $1.5 million David vs. the $40 billion Goliath

The challenge isn’t just code; it’s also capital. While OpenAI scales with billions in compute, African startups are operating on a fraction of the budget. For context, Zuri Health’s only disclosed major raise was a $1.3 million pre-seed round in 2022, supplemented by smaller seed investments and a $100K grant over 2022–2023 to scale its virtual-first platform across multiple countries. In contrast, OpenAI has secured tens of billions in funding, including a recent $40 billion round that valued the company at roughly $300 billion and committed more than $10 billion in compute infrastructure deals to power next-generation AI.

These startups cannot out-spend OpenAI. To survive, they are out-specialising the giants.

KOYO Navigate, launched in Abuja in 2025, uses an “Uncertainty Engine” that quantifies its own doubt. If a user in Lagos inputs “fever, headache, heavy rain last night,” ChatGPT might cross-reference global flu trends. KOYO’s model cross-references local malaria transmission data and mosquito exposure first. More importantly, it triggers an immediate escalation to a human doctor when it detects its own “blind spots.” Early data shows 84% satisfaction—not because the AI is “smarter,” but because it knows when to stop talking.

Similarly, MyItura bridges the gap between text and physical care. If a user reports symptoms, the AI doesn’t just “chat”; it routes the user to a home test kit for malaria or blood sugar, closing the loop between digital triage and diagnostic proof.

The two-year window

African healthtech has about 24 months to lock in its edge. As ChatGPT Health and other global platforms absorb more diverse data, the advantage of local context will narrow fast. The opportunity lies in building around how 1.4 billion Africans actually seek care: treating those realities as core data, not outliers.

According to the World Bank, roughly 3.5 billion people—44% of the world—live on less than $6.85 a day. For that half of humanity, a $20/month AI subscription isn’t access; it’s exclusion. In Africa, where nearly half of sub-Saharan residents live in poverty and mobile broadband costs over 4% of income, paid AI services are out of reach for most households.

This is where health AI must prove itself as infrastructure, not aspiration. The runway is short. Local startups can’t out-spend OpenAI, but they can out-specialise it. As medical expertise becomes commoditised by AI, the real value shifts from knowing to delivering. The strongest African players will operate less like apps and more like franchises—grounded in trust, language, and community reality.

Another path lies in giving doctors their own tools. We’re entering an era where physicians can vibe-code their own narrow AIs. Startups that help local clinicians create these specialised assistants: ones that understand malaria cycles, genotype testing, or blood panel costs in Kano, will scale faster than any centralised model from San Francisco.

And where OpenAI faces scrutiny for its global data collection, African innovators can win on trust. By keeping data local and tying it directly to patient outcomes rather than the next model update, they build both compliance and credibility.

See also: The race between OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic in 2025: who’s winning the AI revolution?

Get passive updates on African tech & startups

View and choose the stories to interact with on our WhatsApp Channel

ExploreLast updated: January 21, 2026