Azeez Ayanniyi bombed a job interview at a Nigerian AI company in 2023.

They were building text-to-speech systems, but he didn’t make the cut, and they told him they would be in touch. He wasn’t waiting around. “I kind of wanted to prove to myself that you can do this too,” Ayanniyi told Condia.

So he did.

Except that building artificial intelligence solutions in Nigeria is less about figuring out the right algorithm or training a sophisticated model, but more about dealing with low-level problems like the poor state of electricity and sometimes, low standards.

Referring to the lights-out problem, he exclaimed, “Chai, this thing don finish me,” in Nigerian Pidgin English, which he’s incidentally training his model to parse. Ayanniyi’s laptop died halfway through a model training session in his residence at Agbado, Ogun State. He has also scraped Nollywood films for voice data only to end up with a garbage dataset because the subtitles were mistranslated.

“Do these technologies [AI] only work for people with better infrastructure?” he often wondered.

He decided they don’t.

So, the 23-year-old mechanical engineering graduate from the University of Lagos (UNILAG) spent most of 2024 building YarnGPT, a text-to-speech system for Nigerian accents and languages: Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa, and Pidgin, a specific strain of English that existing AI models don’t yet get right.

What started as a way to prove a point to himself has attracted over 1,500 active users, sparked conversations with a major Nigerian telecom, and shown what building AI tools looks like without Silicon Valley’s funding or infrastructure.

Despite its usage, the model is still a work in progress. Ayanniyi rates it an 8 out of 10, as the model still cuts words short sometimes. However, this story is more about the constraints shaping AI development in Africa, and whether those constraints are barriers or filters separating people who talk about building from people who build anyway.

What it takes to build a text-to-speech model

Over the past two years, text-to-speech (TTS) technology has evolved from the stilted monotone of early accessibility tools into lifelike voices that breathe, pause, and emote. Companies like ElevenLabs have turned human-sounding audio into an everyday commodity, powering audiobooks, news articles, and learning platforms that can speak in dozens of languages at once. The global TTS market is already worth over $3 billion and projected to reach $47 billion by 2034. For publishers, adding a “listen” button has doubled the average time readers spend on a page. The infrastructure for a voice-first internet is already here.

But Nigeria, and most of Africa, is barely audible in it. The few models that claim to handle African languages still stumble over tonal complexity, code-switching, and rhythm. Most are closed-source or priced out of reach for small creators. “People use ElevenLabs for Nigerian voiceovers,” Ayanniyi says. “It sounds fine, but it’s not us. The cadence, the phrasing—it always feels slightly off.”

That gap is both technical and structural. Speech datasets for African languages are scarce and often messy. Cloud training that costs a few dollars in Europe can drain a developer’s entire monthly savings in Nigeria. Research funding flows toward high-resource languages like English and Mandarin, leaving others to rely on community data collection and personal sacrifice. The result is a global AI economy where some regions aren’t left out by ability but by affordability.

Ayanniyi felt that firsthand after failing a job interview at a local AI startup. They were working on text-to-speech, the very thing he now builds. “It was motivation,” he says. “If they could do it, I could figure it out too.”

Where it all began for Azeez Ayanniyi

Ayanniyi’s first contact with machine learning happened almost by chance. In his first year at the University of Lagos, he joined the Developer Student Club (DSC)—now known as Google Developer Student Club (GDSC) after a global rebrand. It was less about grades and more about curiosity. He’d grown tired of studying only to pass exams, a rhythm that defined school life for most people. “Everyone was reading for tests,” he says, “but I wanted to build something” for four years.

At one of those club sessions, someone mentioned machine learning. The name clicked. Studying mechanical engineering, he figured the two must connect somehow. “Mechanical, machine; they must be related,” he says, laughing. “That’s how I started.”

When COVID-19 sent students home, he turned the lockdown into a lab. Agbado’s erratic power meant he often coded on his phone, saving his laptop battery for when light returned. His education came entirely from YouTube tutorials and online forums: no mentors, no structured lessons, just hours of trial, error, and persistence.

By late 2023, after watching a tutorial on text-to-speech systems, he began experimenting with one that could handle Nigerian accents. Gathering the right data became the hardest part. “If I spent 100 hours on the project, 95 went into collecting data,” he says.

He scraped what he could from Nollywood’s 2,500 yearly films on YouTube, but bad subtitles and uneven audio made most of it unusable. He mixed the salvageable clips with open datasets from Hugging Face, blending Nigerian voices with cleaner speech samples to make the training data work. To train the model, he needed 24-hour runs—something Agbado’s electricity couldn’t guarantee—so he worked from his father’s office in Ogun state or snuck back into UNILAG long after graduation for stable power.

The first version, released in January 2023, spoke with a Nigerian accent but stumbled over words. He shelved it, finished his degree, and took an AI engineering job, but the idea kept calling back. Eventually, he returned to YarnGPT months later with a new principle: if people wouldn’t pay to use it, it wasn’t good enough yet.

The pain of building v1 of YarnGPT from Nigeria

Training an AI model mostly means paying for hardware that most Nigerian developers don’t own. Ayanniyi didn’t own a GPU, the high-performance chip that makes deep learning possible, so he rented time on Google Colab. Each hour came with a cost. His first serious training consumed $50 (~₦80,000) worth of cloud credits, in a country where the minimum wage is ₦77,000, yet the model training produced nothing usable. “The model wasn’t working, and the credit was gone,” he recalls. “That thing pained me.”

With no budget left for trial and error, he looked for alternatives and discovered Oute AI, which had built a text-to-speech system using an autoregressive approach. Instead of processing whole sentences at once, the model learns one fragment at a time, predicting the next piece based on the last—similar to how humans form words in conversation. Using this principle, Ayanniyi adapted an open-source language model, SmolLM2-360M from Hugging Face, and spent another $50 running a three-day training cycle.

This time, the laptop sang back. The first test already carried the inflexion of a Nigerian accent: rough, imperfect, but recognisably homegrown. He kept refining it, sometimes running the same script for hours until the voice began to sound more human and less stitched together.

The toughest part, he explains, wasn’t coding but tokenising audio—breaking long speech into tiny, measurable parts the computer could later reassemble. “It’s like cutting a full song into thousands of clips and then teaching the system to piece it back together in rhythm.”

Today, he rates YarnGPT an 8 out of 10. The model still shortens longer sentences and needs more natural pauses, but it can already speak Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa, and Nigerian English with confidence. “I want it to sound so real that if you listen, you won’t ever guess it’s AI,” Ayanniyi says quietly, a statement that’s both an ambition and a promise. But not being able to decipher if something is machine or human is every developer’s dream, as that makes their solution pass the Turing test.

The toolkit for AI that sounds like home

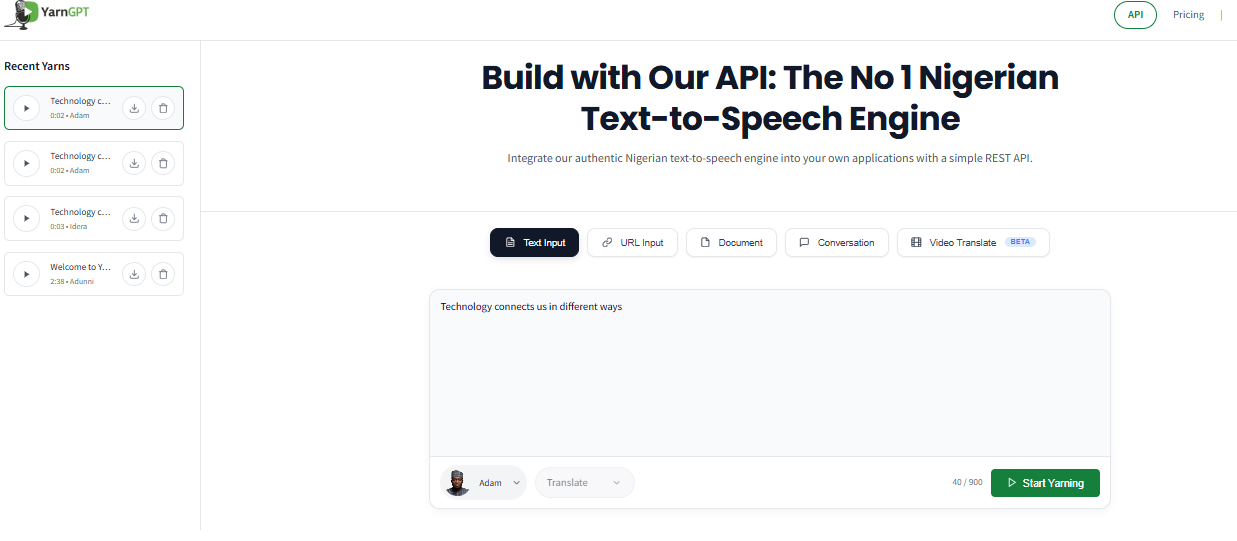

Version 2 of YarnGPT launched in November 2024 with four main features: converting typed text into audio, reading and vocalising web pages, turning PDFs into speech, and dubbing videos into Yoruba, Igbo, or Hausa. The interface is simple: type or upload content, select a language, and get audio within a minute. Videos take longer, and the platform emails a download link when ready.

Ayanniyi built YarnGPT for Nigerian creators tired of generic ElevenLabs voices, but the use cases multiplied quickly. Publishers started asking about embedding audio readers on their sites, a move that aligns with broader trends showing that readers spend nearly twice as long on articles when they have the option to listen instead of scroll. One telecom explored using YarnGPT for customer service in multiple Nigerian languages, and within the first week, ten developers built new applications on top of the API — tools Ayanniyi hadn’t imagined and couldn’t have built alone.

Currently, each user gets 80 free requests per day, limited by server costs rather than strategy. Pricing will come later, set low enough for individual creators but sustainable for hosting and gradual growth. Ayanniyi won’t charge until the model hits the performance standards he’s set. This creates a cycle: improving the product costs money, but revenue is needed to improve it, so scaling carefully is key.

Feedback has been largely positive, with one repeated issue: the model sometimes cuts the last word short on long sentences. Code-switching support, for Nigerian-style mixing of English with local languages, is in progress and will require new training data. Lip-syncing is not yet addressed, but Ayanniyi focuses first on improving the core model. He knows that spreading effort across too many features leads to mediocrity, and he prefers a few strong features over a bunch of half-baked ones.

On scaling YarnGPT

Ayanniyi wants YarnGPT everywhere: on every blog, powering customer service in multiple languages, and helping publishers turn text into audio without extra cost. To make that vision real, he’s focused on refining the technology—fixing word-cutting, enabling code-switching, and making speech sound fully natural. At the same time, he’s taking a strategic approach: rather than competing with global labs, he’s localising existing open-source models for Nigerian languages and accents, adapting world-class tools to fit a distinctly Nigerian context.

Bringing YarnGPT to scale means juggling the technical with the practical. Reliable power, clean datasets, and user adoption all shape how quickly the platform can grow. Nollywood films provide raw material for training, supplemented with open-source speech datasets, while campus facilities offer stable electricity for longer model runs. Meanwhile, Ayanniyi balances development with building a foundation for broader adoption—talking to potential co-founders, engaging early users, and exploring partnerships—so that YarnGPT can expand beyond a single person’s effort.

Early results show traction but not yet revenue. 1,500 users, ongoing API integrations, and discussions with a major telecom signal demand, though the platform remains free while Ayanniyi refines it. For him, scaling is a matter of focus and iteration. His advice to fellow builders is simple: start, adapt, and keep moving. YarnGPT has no limits, and the work between starting and reaching everywhere is exactly where its future will be decided.

Get passive updates on African tech & startups

View and choose the stories to interact with on our WhatsApp Channel

ExploreLast updated: December 3, 2025