In Nigeria, credit or loans to the common man hardly come from the banks. It comes from the social circles of men and women who contribute retail amounts periodically for members to take turns in cashing out the entire pot. This banking (savings and lending) model is called Ajo, or Esusu—a financial system that has survived everything Nigeria could throw at it: colonial rule, military coups, economic crashes, and the rise of modern banking. While banks came and went, failed and merged, Ajo quietly kept Nigeria’s informal economy running.

Salami Omoniyi has spent the better part of eight years trying to prove that this ancient system could work even better with the right structure. On a Wednesday morning in Kaduna, he reviews loan applications from market women across northern Nigeria, while his wife Olubumisola sits beside him, calculator in hand, double-checking figures. Each file represents a woman’s shop restocked, a family’s bills paid, a promise kept. Through their microfinance bank, NEAT, the couple now serves 25,000 borrowers across four states—people long shut out by traditional banks but sustained by the informal economy.

It’s the kind of work that could seem routine—paperwork, calculations, signatures—until you hear Omoniyi talk about how it all started. His voice lights up, the kind of enthusiasm that makes you understand how someone convinces 25,000 people to trust them with their financial futures.

For him, the story always begins with his mother, who sold budget items in their neighbourhood while struggling against a system that favoured those with capital over those with character. Out of that memory came NEAT Microfinance Bank (MfB), which he and his wife founded eight years ago. Today, they run 16 branches across four states, managing a ₦1.5 billion portfolio with non-performing loans under 5%.

But the real proof isn’t in the numbers. It’s in what they’ve shown the industry: that sustainable microfinance doesn’t come from charity or venture capital, and it certainly isn’t a fintech fairy tale. It comes from showing up, week after week, in markets where hope has been rationed as carefully as seasoning cubes.

NEAT is the Ajo that grew up

By 2016, Kaduna’s economy was in flux. Textile mills had gone silent, Peugeot’s plant was shrinking, and oil refineries were fading out, leaving thousands to hustle in undeclared work. For the Omoniyis, it was the moment to try microfinance on their own terms.

They had applied for a ₦20 million license and gotten nowhere. So they pooled ₦250,000—just enough to buy a secondhand car in 2016—and walked into Kasuan Dole market in Kurmi Mashi, Kaduna. Salami took the stalls, handing out loans and collecting repayments, while Olubunmisola stayed on the books. Their first borrowers were five women selling food and fabric.

“I was the marketer,” he says. “She was the accountant.”

What they built wasn’t the polished, app-driven model of savings and credit that Carbon popularised. It was something older, closer to ajo—the rotating credit circles markets have run for generations—only given a sturdier frame. NEAT added regular monitoring, business lessons, and savings rules—so trust didn’t rest on community pressure alone, but on structure too.

“This is group lending, and they know each other very well,” Omoniyi says. “If one person refuses to pay, the whole group feels it. That’s why they’re careful about who joins them.” That self-selection, backed by NEAT’s training and rules, cut most credit risks before a naira left their hands.

Where’s the tech in NEAT?

NEAT’s technology strategy rests on a simple reality often overlooked by flashy fintechs: most borrowers in northern Nigeria’s markets still carry basic feature phones, aka palasa, smartphones. Instead of forcing them online, NEAT equips its 200 field agents with Android devices running proprietary software that captures borrower data, processes loans, and manages repayments in real time.

The system connects with banking APIs to check BVNs and assess risk instantly, while customers stay focused on their trade.

“Most of our customers cannot use applications. But we are using technology internally,” Omoniyi says.

The model only works because NEAT also partnered with banks to ensure every borrower has a functional account and wallet. Disbursements land digitally, and repayments can be made through nearby PoS agents.

This model of back-office tech and front-facing human interaction has proven to Omoniyi and Olubumisola that financial inclusion is better achieved when tech supports, not replaces, relationships.

Sustainable credit in practice

NEAT’s pricing model shows how lending can be both profitable and ethical. They charge 24% interest over six months (1% weekly), well below the 16–18% annual rates charged by most commercial banks in 2024 and 2025. But the real distinction lies in how they design loans around actual business profitability.

“We ensure that the financial intervention we are giving allows them to make profits enough that whatever we are charging as markup will not be more than 30% of the profit they make. If we don’t find that out, we keep working with them until we find a way to make it work before we release the money,” Omoniyi explains.

A typical case would be: a customer receives ₦100,000 ($64) to buy bread wholesale at ₦1,000 ($0.65) per loaf, selling each for ₦1,200–₦1,300 ($0.77–$0.84). That leaves a margin of ₦200–₦300 per loaf, or about ₦20,000–₦30,000 ($13–$19) profit per cycle. Against this, the weekly repayment of roughly ₦5,167 ($3.3) is easily absorbed, allowing the business to grow steadily.

“The ₦24,000 profit we earn over six months is what they can make in a single day,” Omoniyi notes. This is not charity—it is structured business development that creates value for both lender and borrower.

The results reflect this approach: over 55,000 women funded, ₦6 billion disbursed, and non-performing loans consistently below 5%. Most customers complete 12 to 14 loan cycles, evidence of real business expansion rather than debt dependency.

“Cascador gave us more than funding”

NEAT’s journey from an informal lender to a regulated microfinance bank accelerated when Omoniyi joined Cascador’s 2020 cohort. At the time, the company had 4,000 customers and ₦200 million in loans, but little in the way of a framework to scale. “Most of our policies were not written down. Most of our procedures were not documented. We were just running the business with prudence and passion,” he recalls.

Cascador helped close that gap. “Within six months, they connected us with faculty—people who could pick up the phone and open doors to the institutions we needed,” Omoniyi says. For him, Cascador’s ₦500 million catalytic loan is more than money. “The funding is fantastic, but the real value is the support and structure they bring.”

That structure is now visible in NEAT’s operations: 25,000 active borrowers across 16 branches (out of more than 55,000 clients served since inception), with non-performing loans under 5% even through COVID-19 and Nigeria’s cash scarcity crisis. More than efficiency, it gives NEAT the governance and stability to serve vulnerable financial populations with confidence—at rates and structures designed to be sustainable rather than exploitative.

“We love structure,” adds Olubumisola. “It’s what keeps this work clean.”

Community banking for a changing Kaduna

The Microfinance bank’s rise mirrors Kaduna’s economic transformation. Once Nigeria’s industrial capital, the state has moved toward services, agriculture, and technology since the decline of its manufacturing plants, creating huge demand for small business financing that banks couldn’t meet. Today, Kaduna is home to innovation hubs, agri-tech startups, and smart city projects, while still relying on the informal trading networks that drive its markets.

NEAT operates at the center of this hybrid economy, linking traditional traders with modern financial tools. With a footprint across Kaduna, Kano, Abuja, and Kwara, the company sits inside northern Nigeria’s largest commercial networks while keeping the community trust that sustain loyalty. What sets NEAT apart ist its belief that sustainable growth requires more than capital. Their weekly gatherings double as business clinics, literacy workshops, and spaces for peer support.

“We don’t just give loans. We teach people what to do, and sometimes even come to them for disbursement or collection. It’s more than money—it’s service.”

This relationship-driven model keeps customers saving, borrowing, and growing with NEAT for years. More than capital, they offer continuity, proving that financial inclusion can scale through community-rooted models—without massive venture backing or chasing unicorn valuations.

The future of human-centred finance

Looking ahead, NEAT plans to deepen its use of technology while keeping relationships at the heart of its model. They’re building more sophisticated credit scoring systems and exploring partnerships with larger financial institutions for funding and services. At the same time, expansion isn’t straightforward. Each new market requires months of trust-building and staff training, and while technology can make operations smoother, it can’t replace the human connections that keep the system running.

Competition from digital-first lenders adds pressure to go fully online, but NEAT’s customers still value the personal touch of weekly meetings. Economic shifts also test their resilience—currency swings, inflation, and cash scarcity policies have all disrupted operations in recent years. Yet through it all, they’ve stayed profitable, thanks in part to the digital tools they already use to keep payments flowing.

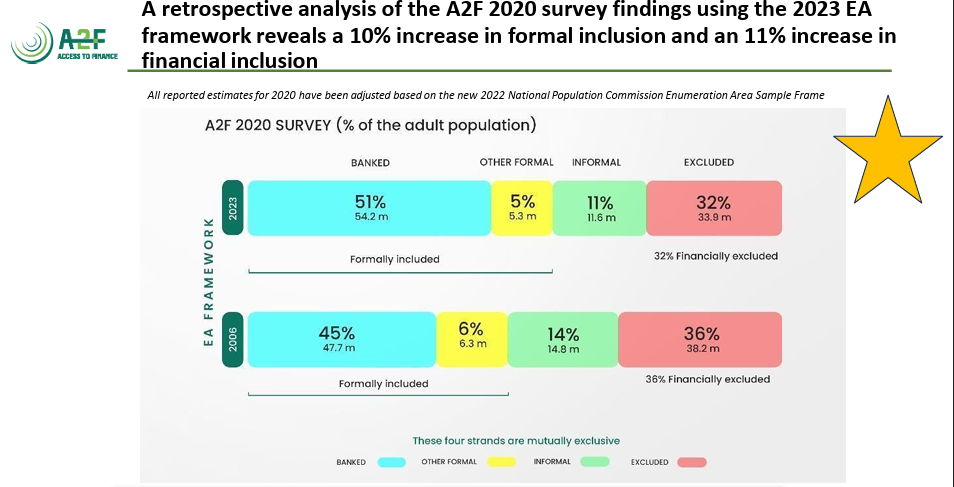

Rather than chasing expensive full banking licenses, NEAT works under state money-lending permits while moving toward microfinance authorisation, a path that allows them to grow without losing their customer-first focus. For a country where about a quarter of adults remain unbanked, their model shows what financial services can look like for people left out of traditional banking.

Omoniyi puts it simply: “I have never believed in charity, like just giving people things, because I understand that no country develops on charity. I believe in helping people, but it has to be sustainable.”

The boy who once watched his mother portion out Maggi cubes now runs an institution reshaping the financial lives of more than 25,000 families. In Nigeria’s turbulent financial landscape, NEAT is building a kind of social infrastructure—one meeting and one Android phone at a time.

Note: EFInA’s “financially excluded” measure is broader than just being “unbanked.” It differs from the World Bank’s Findex definition of people with “no account,” so caution is needed when comparing across sources.

Get passive updates on African tech & startups

View and choose the stories to interact with on our WhatsApp Channel

Explore